–>

|

| The molecular structure of botulinum toxin |

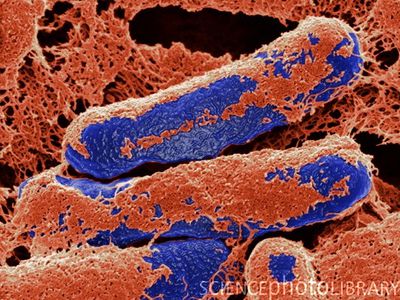

What do foodborne illnesses, neck dystonia treatments, and celebrities’ beauty regimens have in common? Clostridium botulinum, baratii, and other species of Clostridium bacteria produce all of the above and more. These seemingly innocuous, rod-shaped bacteria, commonly found in soil and in the intestinal tracts of fish and mammals, produce one of the most deadly biological substances: botulinum toxin, a neurotoxin that intercepts neurotransmitters and paralyzes muscles in the disease known as botulism. Nonetheless, botulinum toxin isn’t all bad: this chemical not only protects the bacteria from intense heat and high acidity, but it makes for an effective treatment for medical conditions as wide-ranging as muscle spasms, chronic migraines, and, yes, wrinkles.

|

| C. botulinum |

Clostridium botulinum and similar bacteria can make their way into the human body in a number of ways. Wounds infected with Clostridium botulinum or spores ingested by infants can lead to the rare but serious disease of botulism, as can accidental overdoses of medicinal or cosmetic botulinum toxin. Botulism is often foodborne, usually contracted by infants from honey or by adults from improperly home-canned foods and unrefrigerated herb-infused oils. Regardless of where any case of botulism comes from, it causes muscle paralysis, which can manifest as blurred vision, dry mouth, and muscle weakness in adults or lethargy and constipation in infants. These are only early warning signs for an illness that, if left untreated, can paralyze a patient’s respiratory muscles to the point of asphyxiation. Although 95-97% of botulism patients receive treatment and survive, they often require months of intensive care and suffer years of muscle weakness, fatigue, and shortness of breath.

So how does the neurotoxin that makes botulism so deadly work? Clostridium bacteria produce several protein compounds with similar structures and molecular weights, consisting of two chains of amino acids—one small and one large. These two amino acid chains are linked together by a covalent bond between two sulfur atoms, one in each chain. The botulinum toxin proteins bind to nerve endings where they join muscles, blocking the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which ordinarily causes muscle contractions. This blockage is permanent, paralyzing the muscle until a new nerve ending forms a synaptic connection with it. Because the process of forming new neuromuscular junctions takes at least 2 or 3 months, the affected muscle will often atrophy in the meantime, causing the long-term side effects that plague botulism survivors.

Ironically, the very mechanisms that make botulinum toxin so dangerous give it a wide range of beneficial medical applications. When botulinum toxin is administered in small, controlled doses, its muscle-contraction preventing effects make it a viable treatment for neck dystonia, sustained involuntary eyelid closure, chronic migraines, neurogenic bladder dysfunction, and other conditions caused by involuntary muscle movements. In popular culture and tabloid media, Botox’s serious medical applications are often overshadowed by its cosmetic notoriety: smoothing out wrinkles. Cosmetic Botox inhibits the neuromuscular activity that leads to wrinkles, relaxing the surrounding skin. Seeming to reverse one of the telltale signs of aging may have given botulinum toxin its Hollywood appeal, but its wide ranging pharmaceutical uses are what continue to fascinate research scientists.

In a nutshell, the molecule botulinum toxin is a toxic protein made by clostridium botulinum bacteria. In measured amounts, the toxic protein is marketed as Botox for pharmaceutical uses. When uncontrolled doses of the bacteria are ingested, however, Clostridium botulinum can result in deadly cases of muscle paralysis called botulism.

If you are intrigued by the terrible beauty of such a versatile molecule as botulinum toxin, come to Marin Science Seminar on September 30th, at Terra Linda High School, 320 Nova Albion Way, in Room 207 from 7:30 to 8:30 pm, when bioanalysis and pharmacology expert Dr. Erik Foehr will discuss his research on botulinum toxin.

Sources: http://emedicine.medscape.com

Images: