Almost everyone has seen a coral reef. Whether immersed in the warm waters of the tropics, or staring wistfully at the enticing commercials on television, the gently waving anemones and the masquerade of tropical fish have long been lauded as one of the most beautiful sights in the world.

However, the amount of healthy coral reefs is decreasing rapidly. Pictures of colorful corals populated with their lively inhabitants are becoming less and less representative as coral reefs are systematically destroyed worldwide. Images of barren seafloors, strewn with bone-white coral remains and not a single fish in sight are becoming more and more accurate.

So, why are coral reefs disappearing? Dynamite fishing, trawling, tourism, and global warming all take some responsibility.

Dynamite fishing is exactly what it sounds like—using explosives to stun and capture fish. It has a severe and very literal impact on coral reefs, blasting the polyps to shreds and reducing the homes of thousands of sea creatures to litter in seconds. The dangers of dynamite fishing (also known as blast fishing) are well known and outlawed in most countries, but the illegal practice remains predominant in several countries.

Trawling damages coral reefs in a similar manner. By dragging a net over the sea floor, fishermen get the fish they want—plus their coral-rock homes and all of their unhappy, inedible neighbors. By casting such a wide net, trawling not only bulldozes coral reefs away, but also threatens multiple fish populations as unwanted fish are dumped away or displaced.

Both of the aforementioned fishing practices are spurred by the immense seafood industry. In more developed countries, fish farms and specifically allotted areas for fishing manages overfishing problems and avoids damaging wild ecosystems. But in underdeveloped countries, where fishing is the only livelihood on the coast and equipment for more accurate, less invasive fishing practices is nonexistent, people turn to trawling and dynamite fishing. No one can blame them for needing to feed their family, but funding outreach programs can bring the technology and technical instruction countries need to stop destroying valuable ecosystems that sustain more species than classy couples eating out at their favorite upscale seafood bistro.

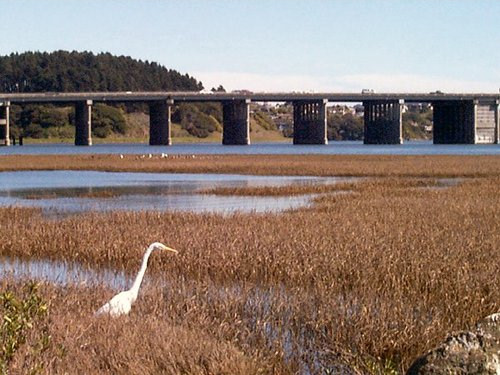

Tourism presents similar challenges. Though a lucrative business, (and sometimes a nation’s sole business), tourists may litter or “take souvenirs” from coral reefs. The upkeep of tourist towns, including waste from hotels and shacks selling tourist goods like painted starfish or other artifacts from the oceans serves to pollute/damage the coral reefs that sustain the entire business. Some areas have begun offering ecotourism as an alternative to the often harrowing consequences of mainstream tourism. Ecotourism differs from widespread tourism in that its goal is to not only tour beautiful sights, but to do so in a non-intrusive way. Ecotourism also aims to educate tourists in environmental conservation, respect for cultural heritage, and other methods and attitudes in which people can preserve the natural wonders of the world.

Global warming, which has already affected yearly temperatures, migration patterns, and much more, is also affecting the underwater scene. Just as a few degrees of temperature difference on land can be disastrous for humankind, a single degree of temperature difference underwater has already caused thousands of coral reefs to die out. Under the stress of warmer temperatures, the sensitive corals expunge the colorful algae living in them. The coral then turns white and very often dies, in a process called ‘coral bleaching.’ Entire systems of reefs have been bleached because of global warming. Warmer temperatures also means an increase in disease amongst corals, like the black band and white band disease.

Another effect of global warming is ocean acidification. As greenhouse gases increase, the natural absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere becomes more burdensome on the ocean. Sea creatures thrive on the calcium carbonate in the ocean water, which is used to build shells and, in the case of corals, skeletons for coral growth. When carbon dioxide enters the ocean, it reacts with the water and carbonate ions to form bicarbonate ions. The subsequent acidification and lack of carbonate ions means shellfish construct thinner shells, corals cannot build, and sea life becomes more vulnerable in general.

There’s a lot riding on coral reefs. Biodiversity: the ingenious genes, physiological processes, and chemical compositions each specific species holds, is key to developing better medicines and cures for human diseases. Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots. Tourism is the lifeline of several countries such as many in the Caribbean, and constitutes a large chunk of income for other countries, such as Australia and its Great Barrier Reef. The destruction of reefs would hurt the economy of these and other nations.

A lot of everyday ways people can help tie in with the general problem of environmental conservation: recycle, conserve energy, reduce emissions by carpooling and using public transport, buy from companies that have ecologically safe practices, and keep voting for greener policies. It would be a shame if, in our haste to survive above shore, we suffocate life under the surface.

—

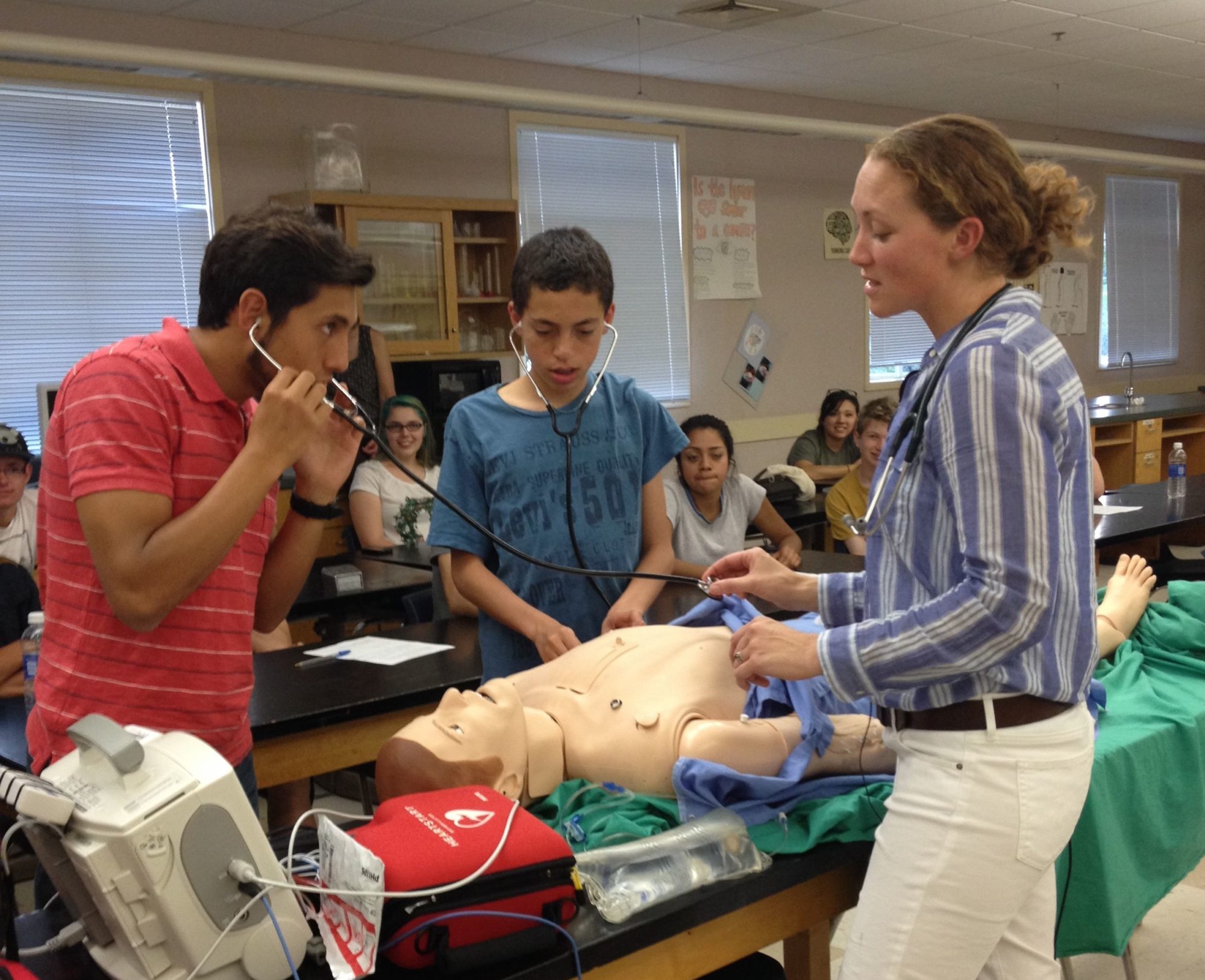

Come see Dr. Vania Coelho, Ph.D and professor at Dominican University, present ‘Homeless Nemo: What does the Future Hold for Coral Reef Communities?’ at Terra Linda High School, room 207, on Wed., February 13th. The Marin Science Seminar starts at 7:30 and ends at 8:30. Check out our website and Facebook!

—

Sandra Ning