The first thing young students learn about space in their science classes is that it is huge. Earth becomes a speck in the solar system, infinitesimally small compared to the hulking gas giants orbiting ponderously outside of the asteroid belt, and infinitely distant from the roiling surface of the Sun. The solar system becomes a speck in the eye of the Milky Way galaxy: the heat of the Sun, too bright for humans to even look at, becomes mediocre in the face of thousands of other brighter, white-blue stars dotting the galaxy. Red dwarves overshadow even the largest planet, Jupiter. Even the harmonic system of the Sun and its orbiting planets is just one out of an incredible number of star clusters, constellations, distant planets and binary stars that comprise our galaxy.

At the point when the solar system is only an afterthought on a distant arm of the Milky Way galaxy, and when the Milky Way becomes only one galaxy in an innumerable number within the universe, just about everyone begins to feel a little small.

The good news is that there’s something smaller than little Earth and its inhabitants out in space. What might be considered bad news is that these innocuous little phenomena are the sucking, inescapable vortices of extreme gravitational pull that inevitably show up in every science-fiction novel: black holes.

The smallest black holes are thought to be as small as a marble, or even an atom. Yet, packed within black holes, is compressed, super-dense matter that results in a gravitational field around it that is so strong not even light can escape its grasp— hence the black hole’s invisibility in front of the searching eyes of telescopes.

In actuality, the sizes of black holes fall into three categories: small, stellar, and supermassive. The smallest are thought to have formed during the birth of the universe, and pack literally tons of matter into areas that are very small. The result is, of course, the extreme density and gravitational field that characterize black holes.

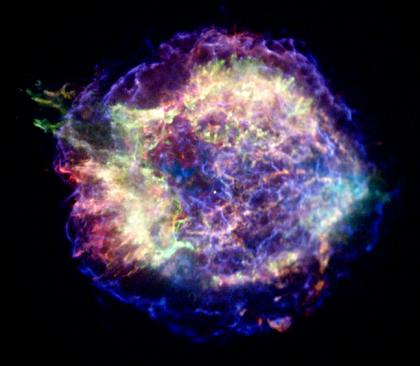

“Stellar” black holes are about the size of a star, and can be up to twenty times the size of the Sun. These black holes form when very large stars collapse and create a supernova explosion. Gravity and atomic forces are always at odds around any object in space. The mass of the object creates a gravitational pull that acts on the object, but the object’s core atomic and nuclear energy are often stronger and allow the object to resist being crushed by its own gravity. At times, though, massive stars near the end of their lifespan don’t have enough thermonuclear force to resist the incredible force of gravity their mass gives them.

The star thus collapses under the force of gravity, and explodes in what is known as a supernova. Bits of the star’s gases go flying in this spectacular event, creating the fire-like nebulae observatories sometimes capture in photos. The rest of the collapsing star gets crushed by gravity into an area smaller than the massive star, but a mass similar to that of the massive star.

“Supermassive” black holes are, true to their name, incredibly large black holes that are often over one million times the size of the Sun. These black holes are, for reasons currently still being studied, found at the center of spiral galaxies; supermassive black holes are thought to be created around the same time the surrounding galaxy was formed. The supermassive black hole believed to be at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, known as Sagittarius A*, is as big as four million suns.

Black holes are not as sinister or dangerous as science fiction novels tend to suggest. Consider the universe as one, large fabric of ‘space-time,’ as Einstein imagined it. The Sun creates a sizable depression in the fabric with its mass, and the dip in the fabric is the gravitational pull that the orbiting planets around the Sun experience. Now, holding the same mass but with the volume of a penny, black holes are far smaller and far denser than the Sun. Placing one into the fabric of space-time creates a narrow, but deep depression in the fabric. This accounts for the inescapable gravitational force a black hole has. But outside of its narrow tunnel of gravitational pull, the fabric appears normal. In other words, gravity around a black hole is normal. Gravity only becomes an inescapable pull when matter passes the surface of the black hole—this point of distance to the black hole is known as the event horizon.

What matter gets sucked into is known as the singularity of a black hole. The center of a black hole, the singularity, is the point where matter is compressed into infinite density. The gravitational pull is infinite, and space-time ceases to exist meaningfully. All nebulae, planets, asteroids and stars that get pulled into the center of a black hole are crushed and exist in some timeless, spaceless, inescapable space purgatory.

Or do they? Beyond the event horizon of a black hole, scientists don’t really know for sure what happens inside of a black hole. Any foray into a black hole would never make it back to Earth, and the pull black holes have on light make it impossible for telescopes to study a black hole directly; scientists deduce the existence of black holes mainly through examining the orbits of objects in space around it. Because of this inability to study black holes more closely, black holes remain very mysterious.

Luckily for humankind, no black holes exist even close to Earth. It begins to feel a little luckier, sitting on the edge of the Milky Way galaxy, far away from the mysterious, roiling center where Sagittarius A* looms. But just considering their properties— a gravitational force that dominates even the speed of light, the spectacular origins of stellar black holes, and the curious centrality every supermassive black hole holds in each galaxy— it’s no wonder black holes capture the attention of scientists, authors, and the everyday student so easily. One might say that the study of black holes has at least metaphorically sucked in humankind.

—

Curious about black holes? Come join the Marin Science Seminar for Dr. Eliot Quataert’s presentation, ‘Black Holes: The Science Behind Science Fiction,’ tomorrow on Wednesday, March 13th. The Marin Science Seminar is located at Terra Linda High School, in room 207, from 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. Check us out on Facebook!

—

Sandra Ning